Why Arguments Polarize Us

(1400 words; 7 minute read.)

The most important factor that drove Becca and me apart, politically, is that we went our separate ways, socially. I went to a liberal university in a city; she went to a conservative college in the country. I made mostly-liberal friends and listened to mostly-liberal professors; she made mostly-conservative friends and listened to mostly-conservative ones.

As we did so, our opinions underwent a large-scale version of the group polarization effect: the tendency for group discussions amongst like-minded individuals to lead to opinions that are more homogenous and more extreme in the same direction as their initial inclination.

The predominant force that drives the group polarization effect is simple: discussion amongst like-minded individuals involves sharing like-minded arguments. (For more on the effect of social influence, see this post.)

Spending time with liberals, I was exposed to a predominance of liberal arguments; as a result, I become more liberal. Vice versa for Becca.

Stated that way, this effect can seem commonsensical: of course it’s reasonable for people in such groups to polarize. For example: I see more arguments in favor of gun control; Becca sees more arguments against them. So there’s nothing puzzling about the fact that, years later, we have wound up with radically different opinions about gun control. Right?

Not so fast.

In 2010, Becca and I each knew where we were heading. I knew that I’d be exposed mainly to arguments in favor of gun control, and that she’d be exposed mainly to arguments against it. At that point, we both had fairly non-committal views about gun rights—meaning that I didn’t expect the liberal arguments I’d witness to be more probative than the conservative arguments she’d witness.

This gives us the puzzle. At a certain level of generality, I know nothing about about gun rights now that I didn’t in 2010. Back then, I knew I’d see arguments in favor, but I was not yet persuaded. Now in 2020 I have seen those arguments, and I am persuaded.

Why the difference? How could receiving the arguments in favor of gun control have a (predictably) different effect on my opinion than predicting that I’d receive such arguments? And given that I could’ve easily gone to a more conservative college and wound up with Becca’s opinions, doesn’t this mean that my current opinion that we need gun control was determined by arbitrary factors. In light of this, how can I maintain my firm belief?

As we’ve seen, ambiguous evidence can in principle offer an answer to these questions. Here I’ll explain how this answer can apply to the group polarization effect.

Begin with a simple question: why do arguments persuade? You might think that’s a silly question—arguments in favor of gun control provide evidence for the value of gun control, and people respond to evidence; so rational people are predictably convinced by arguments. Right?

Wrong. Arguments in favor of gun control don’t necessarily provide evidence for gun control—it depends on how good the argument is!

When someone presents you with an argument for gun control, the total evidence you get is more than just the facts the argument presents; you also get evidence that the person was trying to convince you, and so that they were appealing to the most convincing facts they could think of.

If the facts were more convincing than you expected—say, “Guns are the second-leading cause of death in children”—then you get evidence favoring gun control. But if the facts were less convincing than you expected—say, “Many people think we should ban assault weapons”—then the fact that this was the argument they came up with actually provides evidence against gun control. (H/t Kevin Zollman on October surprises.)

This is a special case of the fact that, when evidence is unambiguous, there’s no way to investigate an issue that you can expect to make your more confident in your opinion.

Why, then, do arguments for a claim predictably shift opinions about it?

My proposal: by generating asymmetries in ambiguity. They make it so that reasons favoring the claim are less ambiguous—and so easier to recognize—than those telling against it.

Here’s an example—about Trump, not gun control.

Argument: “Trump’s foreign policy has been a success. In particular, his norm-breaking personality was needed in order to shift the political consensus about foreign policy and address the growing confrontation between the U.S. and an increasingly aggressive and dictatorial China.”

This is an argument that we should re-elect Trump. Is this a good argument—that is, does it provide evidence in favor of Trump being re-elected?

I’m not sure—the evidence is ambiguous. What I am sure of is that if it is a good argument, then it’s so for relatively straightforward reasons: “Trump’s presidency has had and will have good long-term effects.”

If it’s not a good argument, then it’s for relatively subtle reasons: perhaps we should think, “Is that the best they can come up with?”; perhaps we should think that relations with China were already changing before Trump; perhaps we should be unsure whether inflaming the confrontation is a good thing; etc.

Regardless: if it’s a good argument, it’s easier to recognize as such than if it’s a bad argument As a result, we can expect to be, on average, somewhat persuaded by arguments like this.

As before, it’s entirely possible for this to be so and yet for the argument to satisfy the value of evidence—and, therefore, for us to expect that it’ll make us more accurate to listen to the argument rather than ignore it. At each instant we're given the option to listen to a new argument or not, we should take it if we want to make our beliefs accurate.

And yet, because each argument is predictably (somewhat) persuasive, long periods of exposure to pro (con) arguments can lead to predictable, profound, but rational shifts in opinions.

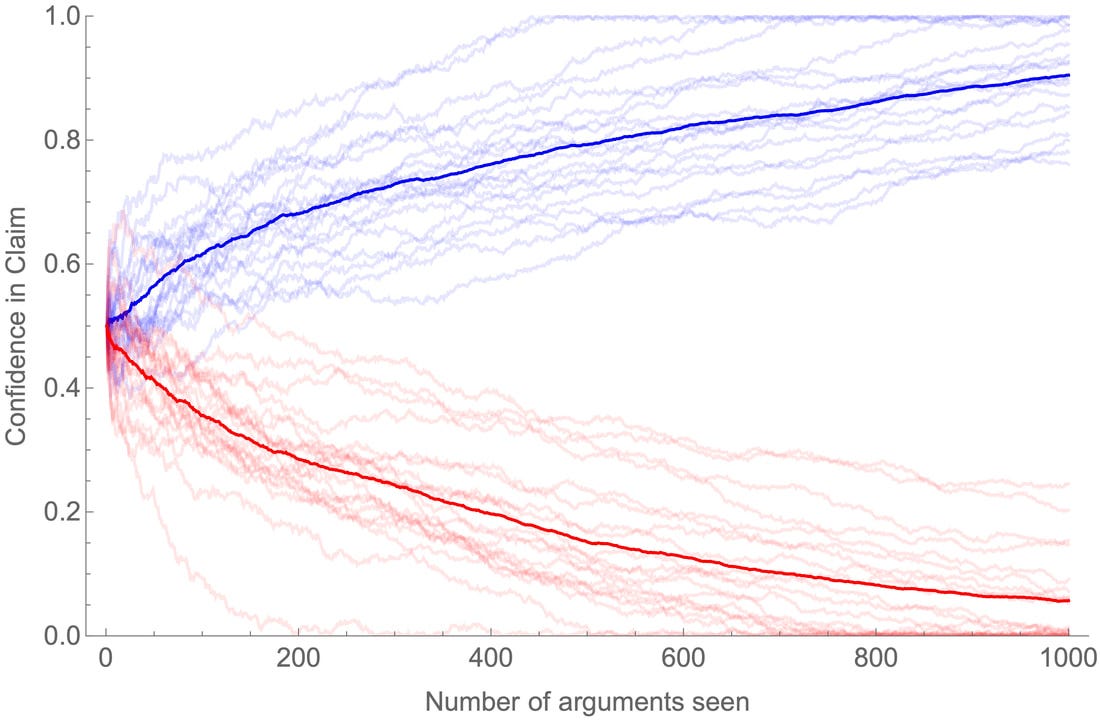

We can model how this worked with me and Becca. The blue group (me and my liberal friends) were exposed to arguments favoring gun control—that is, arguments that were less ambiguous when they supported gun control than when they told against it. The red group (Becca and her conservative friends) were exposed to arguments disfavoring gun control—that is, arguments that were more ambiguous when they supported gun control than when they told against it.

Suppose that, as a matter of fact, 50% of the arguments point in each direction. Because of the asymmetries in our ability to recognize which arguments are good and which are bad, the result is polarization:

Simulation of 20 (blue) agents repeatedly presented with arguments that are less ambiguous when they support Claim, and 20 (red) agents presented with arguments that are less ambiguous when they tell against Claim. In fact, 50% of arguments point in each direction. Thick lines are averages within groups.

Notably, although such ambiguity asymmetries are a force for divergence in opinion, that force can be overcome. In particular, as the proportion of actually-good arguments gets further from 50%, convergence is possible even in the presence of such ambiguity-asymmetries. Here’s what happens when 80% of the arguments provide evidence for gun control:

As above, but this time, in fact, 80% of arguments tell in favor of Claim.

Thus polarization due to differing arguments is not inevitable—but the more conflicted and ambiguous the evidence is, the more likely it is.

How plausible is this as a model of the group polarization effect? Obviously there’s much more to say, but there is indeed some evidence that group-polarization effects—and argumentative persuasion in particular—are driven by ambiguous evidence.

First, the group discussions that induce polarization also tend to reduce the variance in people's opinions, and the amount of group shift in opinion is correlated with the initial variance of opinion.

These effects make sense if ambiguous arguments are driving the process. For: (1) the more ambiguous evidence is, the more variance of opinion we can expect; (2) if what people are doing is coordinating on what to think about various pieces of evidence, we would expect discussion to reduce ambiguity and hence reduce opinion-variance; and (3) the more initial variance there is, the more diverse the initial bodies of evidence were—so the more we should discussion to reveal new arguments, and hence to lead participants to shift their opinions.

Second, participation in the discussion (as opposed to mere observation) heightens the polarization effect, as can merely thinking about an issue—especially if people are trying to think of reasons for or against their position or expecting to have a debate with someone about it.

If what people are doing in such circumstances is formulating arguments (perhaps through a mechanism of cognitive-search), then these are exactly the effects that this sort of model of asymmetrically-ambiguous arguments would predict—for they are in effect exposing themselves to a series of asymmetrically-ambiguous arguments.

Upshot: it is not irrational to be predictably persuaded by (ambiguous) arguments—and the more people separate into like-minded groups, the more this leads to polarization.

What next?

If you liked this post, consider subscribing to the newsletter or spreading the word.

For the details of the models of asymmetrically-ambiguous arguments and the simulations that used them, check out the technical appendix (§7).

Next Post: we'll return to confirmation bias and see how selective search for new information is rational in the context of ambiguous evidence.